There are bad smells I can’t forget. The oily stench of paper mills in Virginia. The burnt metal odor that permeated my Dad’s work clothes, filling my mouth with a mercury taste. The rank cloud mushrooming out of the doorway to one of those public outhouses at northern Pennsylvania rest stops. But then there was the word-defying reek from those early spring days when my Great-grandfather, Fritz, cooked dirt.

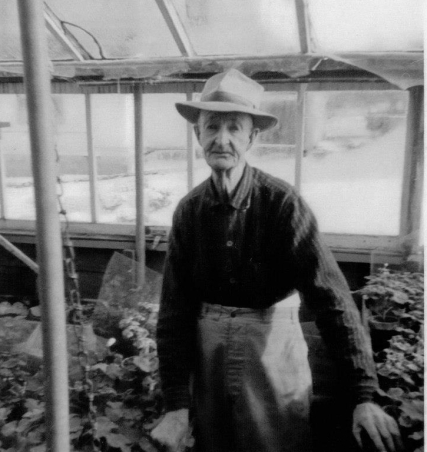

Fritz was 84 years old when I was born. He lived in his own apartment within the family home at 113 Highland Avenue. He had sold the house to my parents at a bargain price, with the agreement that they would provide him, and my father’s mother Ida, a place to live as long as they needed it. I grew up with a house divided into ours (the first floor and one room and closet at the top of the stairs) and theirs (most of the second floor and a greenhouse attached to the kitchen). It was an old frame farmhouse that the initial Hannigans had adapted with little or no carpentry skills.  The kitchen, built on a slab off what was our living room, had a floor that tilted in all four cardinal directions. Fritz’s greenhouse butted up against the kitchen; the two rooms leaned against each other like an old couple facing a hard wind. His greenhouse could not be confused with any of those lovely, glass-coated, light-filled conservatories where flowers scent the air. No. His world was full of dirt and cobwebs, dark wet plank tables, and cans filled with chemicals and powders he could no longer identify. We did not play in the greenhouse; my mother did not step foot in the greenhouse. It was the Geranium Man’s place.

The kitchen, built on a slab off what was our living room, had a floor that tilted in all four cardinal directions. Fritz’s greenhouse butted up against the kitchen; the two rooms leaned against each other like an old couple facing a hard wind. His greenhouse could not be confused with any of those lovely, glass-coated, light-filled conservatories where flowers scent the air. No. His world was full of dirt and cobwebs, dark wet plank tables, and cans filled with chemicals and powders he could no longer identify. We did not play in the greenhouse; my mother did not step foot in the greenhouse. It was the Geranium Man’s place.

Fritz grew geraniums. I don’t know if he started them from seed, or propagated them from cuttings. Geraniums are not particularly difficult to grow, but they progress slowly. The seedlings fall prey to wilts and damp rots, particularly in cool, wet environments. It can take three months to get from seed to blossom, and so Fritz would start his work before spring had even arrived. The winters of the 1960s lasted well into March and even April. To safeguard the tender plants, Fritz needed a sterilized growing medium. If he planted them in pots of garden soil, they would be attacked by any number of molds and mildews, as well as nematodes and other insects. A gas line ran to the greenhouse, and fed a make-shift stove that someone had cobbled together. Over the gas flame, Fritz would cook batches of wet dirt for hours, raising the temperature of the dirt to just shy of 200 degrees and keeping it there for about an hour. Batch followed batch, until he had enough for all the pots he planned to start.

The smell that seeped out of the greenhouse into the kitchen was worse than a dump burning. Worse than the water that collects in the bottom of a trash can in July. Worse than burning hair, or wool, or plastic. My Mom moved into the house on Highland Avenue when she was pregnant with me, and every time Fritz needed to bake dirt, she spent the day vomiting. The fact that she continued to cook and clean for him for thirteen years, even as he routinely stunk up her freshly cleaned house, speaks volumes to the goodness of her heart. But that does not mean that her moods didn’t blacken when the first horrible whiff snuck under the kitchen door. Windows were thrown open, pots and pans were smacked around a little harder than necessary. And we children fled outside to play, preferably upwind.

Fritz was an old man when I was born, and an ancient one in my memories. Small and wiry, there wasn’t an ounce of extra fat on the man. His bald head and hooked nose reminded me of a plucked chicken. Nearly deaf, nearly blind, he spent his days puttering around the greenhouse, or sitting in a chair in his upstairs parlor. By divine whim, I had no normal grandfathers, and only one overworked grandmother who was too busy to fuss over us. Ida didn’t count, as she had never successfully imitated either a mother or a grandmother. I yearned for an older person to take notice of me. Wasn’t that supposed to be part of the deal of being a child? There should have been grandfathers to slip us candy bars and teach us how to skip stones and explain why parents were so damn difficult to live with. But Fritz, while present at every meal, was too old to be that sort of grandfather. I watched him pepper his eggs black. I called him for dinner every day, since I had the loudest yell. I listened to him as he walked slowly down the stairs, his old man murmur of “Ho hum” marking each slow step. But we never sat like two old friends on the couch, or talked about how things worked. I avoided touching him. He was the old man who lived upstairs.

The geraniums grew in the dim greenhouse . Fuzzy green leaves whorled out from stubby stems. He probably grew other colors but I remember most clearly the gorgeous red ones. By Memorial Day, they were ready to decorate the graves, the front porches, and the base of the monument in Memorial Park. Fritz sold them all, to customers who came back year after year, for his special geraniums. I don’t remember if he grew anything else for the remainder of the year. By the beginning of June, our vegetable garden was in full operation — peas and new potatoes would be coming in as early as my birthday, and the tender peppers and tomatoes were safe from frost. The entire summer would be a calendar of what was ripe, and when the freezing and canning would commence. The vegetable gardens were my mother’s domain, and Fritz stayed clear of her wake as we all did.

. Fuzzy green leaves whorled out from stubby stems. He probably grew other colors but I remember most clearly the gorgeous red ones. By Memorial Day, they were ready to decorate the graves, the front porches, and the base of the monument in Memorial Park. Fritz sold them all, to customers who came back year after year, for his special geraniums. I don’t remember if he grew anything else for the remainder of the year. By the beginning of June, our vegetable garden was in full operation — peas and new potatoes would be coming in as early as my birthday, and the tender peppers and tomatoes were safe from frost. The entire summer would be a calendar of what was ripe, and when the freezing and canning would commence. The vegetable gardens were my mother’s domain, and Fritz stayed clear of her wake as we all did.

Fritz grew geraniums until he died, age 96, in October 1971. By then, I had long since given up hope of finding a grandfather figure. I was twelve, practically grown. But in the spring of 1972, as the snows melted and the back yard thawed, no dirt was cooked over the gas stove. Instead my Mother, as always moved by tidal forces only she feels, decided that the greenhouse needed to come down. My parents were planning the first of many remodeling projects for the upcoming year, and a new kitchen was in the works as well. The greenhouse was the first step. So she began ripping it apart and carrying the lumber up to the edge of the woods where we burned things. In her zeal, she caused a general collapse of the wall near the gas line. It snapped and gas filled the air. She yelled for help and luckily one of the neighbors heard her, found the shutoff valve, and Mom went on with the demolition.

Every year I plant a couple of red geraniums, and I usually manage to kill them off before August. I wouldn’t dream of starting one from seed, any more than I would consider preparing my own potting soil. I wonder what Fritz would think of our easy order world. Everything achieved through labor that is not ours. I do not know what he thought of his three little great-granddaughters, and our wild playground outside his greenhouse windows. The Hannigan clan was not known to like children very much, and Fritz might have been at his heart no kinder than his daughter. But then, there was in him something of a genius for coaxing an astonishing beauty out of nothing. A surprising creation for this drab bird of a man.

Gosh, Kim, I had remembered none of this, then, suddenly, all of it, though just in its edges. I remember him. And her. Both, as…surly. And I knew even as a very young child that your mom’s sweet disposition was tempered by them. And I remember the smell! And I remember the new kitchen and how lovely it was, and how well it *worked*. Your mother’s plans set me to examining triangulation patterns in kitchens everywhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! That picture of your grandfather really brought back memories for me.I remember him sitting at the kitchen table and being upstairs. I don’t remember him cooking dirt! I don’t remember the green house. But, I loved getting flowers and plants from Hannigan’s Green House in Belmont when I worked there. They have to be relatives! I remember your Mom as always being sweet and domestic. She was a good woman to take care of Grandpa. He was always kind of a mystery to me. He never really talked to us. He was just there! Keep the stories coming and don’t forget our favorite climbing tree!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fritz’s son George ran the commercial greenhouse in Belmont.

LikeLike

This is unbelievably evocative, of course, but I’m also reacting to never having had any grandparents, and this: “By divine whim, I had no normal grandfathers, and only one overworked grandmother who was too busy to fuss over us. . . . I yearned for an older person to take notice of me. Wasn’t that supposed to be part of the deal of being a child? There should have been grandfathers to slip us candy bars and teach us how to skip stones and explain why parents were so damn difficult to live with.” Perfect. Why didn’t I have that? Why didn’t I really feel I had family? I want that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: October 3/365 My First Ghost – 365/radical elements